Save Kadazandusun language through literature – Dompok

- Wartawan Nabalu News

- Feb 21, 2022

- 8 min read

21 February 2022

By Wartawan Nabalu News

With the passage of time, the Kadazandusun language has diminished and many today see its future challenged as many of the community’s younger generation are struggling to hold a conversation in this language.

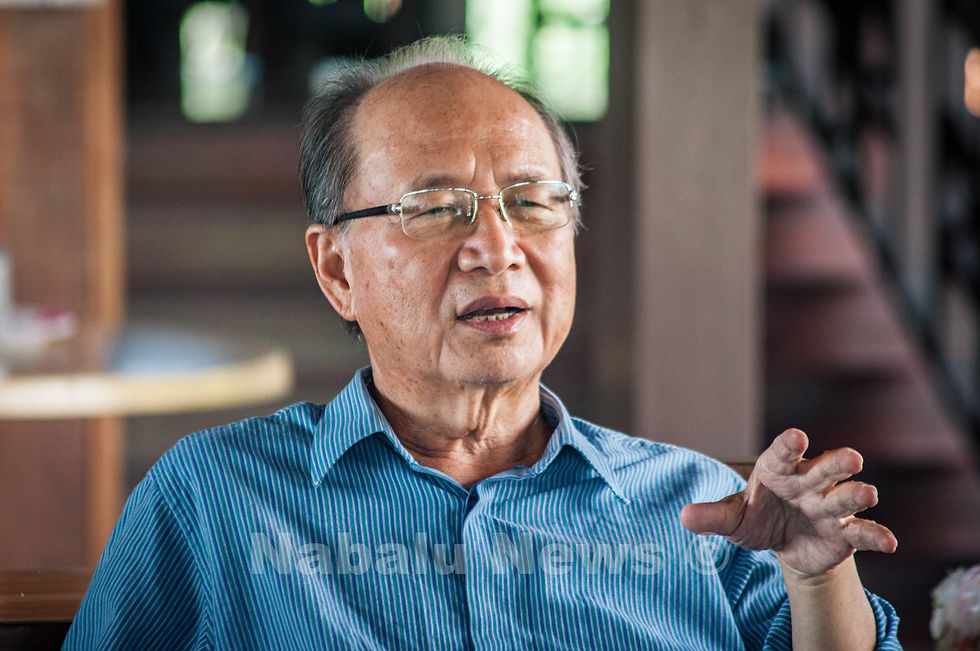

However, Tan Sri Bernard Giluk Dompok – whose name is no stranger to the people of Sabah, especially the Kadazandusun community – said not to fret as there are still ways to save the dear lingo.

It’s important not to give up on this language, he said, as it would become part and parcel of developing a Bornean identity.

Dompok who previously held the presidency of the United Pasokmomogun Kadazandusun Murut Organisation (UPKO – now known as United Progressive Kinabalu Organisation) had fought for the Kadazandusun language to be an official subject in schools starting 1994 but was only approved by the Education Ministry much later.

“There were requests for the language to be accepted into the school curriculum and the government then did not take it seriously. This may have been a contributory factor to the predicament that the language faces today,” he said during an exclusive interview with Nabalu News, recently.

He said that he brought up the matter to the government when he was a minister in the Prime Minister’s Department, during an UPKO Convention, after articulating for the language to take its rightful role among the languages taught in Malaysian schools.

His discussion with the then Deputy Prime Minister, Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, and Minister of Education Tan Sri Sulaiman Daud led to the approval. Dompok recalled that the Minister of Education, a son of Sarawak, remarked that he was giving the approval to save a Borneon Culture.

Even then, he mentioned that there were issues related to the choice of the dialect to be used for the subject. The Education Ministry was worried that there may be a problem if disagreements were to emerge within the community.

The officers suggested a meeting with the Kadazandusun Cultural Association (KDCA) and the United Sabah Dusun Association (USDA). Dompok thought it was a good idea and the ministry subsequently started the discussions which led to the signing of an agreement between Datuk Sri Panglima Joseph Pairin Kitingan and Datuk Mark Koding, representing their respective organisations. They decided to settle for the Bundu Liwan dialect.

However, some recently argued that the Kadazandusun syllabus should adopt the Kadazan Tangara dialect instead, but Dompok said there was no necessity since the Bundu Liwan dialect has long been accepted in the school curriculum and is now almost established.

“There is no need to reinvent the wheel. My own personal view is that dialects like Tangara, Rungus or Tatana for that matter have a place in this language.

“There is already a template done for the Bundu Liwan dialect … There is no need for the Momogun people to quarrel as to which dialect should be used. We should request for example, in the Penampang and Papar districts, for a choice to use the Tangara dialect; Rungus in the Kudat area and so on. The template which is already in use can be utilised for the respective dialects.”

Dompok also observed that many people have shown interest in the uniqueness of the Bornean language, and this can be seen through the introduction of the language not just in schools, but also in universities.

An earlier interest of course was shown among the missionaries who came to Sabah back then, especially in the Penampang and Papar areas.

“They (the missionaries) have started to bring the gospel in the vernacular language and the Tangara dialect can be found in the Bible literature in Ranau and Tambunan, for example,” he said, adding that a passage in the Bible written in Tangara could be autoread in Bundu Liwan.

“Of course, there is a lot to discover in Borneo, the third-largest island in the world, but the last thing that the Momogun people want is a loss of language which will indeed lead to a loss of culture.

“I think it has been my pride and joy to have been able to be part and part of this (language) preservation. It’s a long way but its start is very important,” he said.

“People in my generation didn’t have to worry about their language. I had a classmate who didn’t speak Kadazan at home but mingled with other classmates who spoke Kadazan and later on caught up.

“So, it was possible then to learn Kadazan because it was there in the community, but now things have changed. So many things are happening now that today’s children miss the opportunities that we had while growing up,” he said.

Dompok, referring to the Ainu language in Japan stated: “I was made to understand that there are about 15,000 people who are still called the ‘Ainu’ in Hokkaido, but only about 15 Ainus left that still speak the language.”

He has his fears that at some point, the Kadazandusun language may face the stark reality now in front of the Ainu language if the issue is not addressed accordingly.

“I think through literature, the usage of language will get better. A person interested in learning a language can get into the language faster by reading a book. And indeed, Kadazandusun literature should have a place in schools where Kadazandusun is taught,” he said.

Meanwhile, Dompok opined that the culture and ecosystem are also part of the cause that influences language illiteracy among the younger generation.

The strong influence of international languages such as English and of course in Malaysia, the national language, has led to less opportunity for native languages to flourish.

It could also be that many Kadazandusun youngsters don’t see the need to learn the language as it is not a necessary requirement when it comes to career development.

On this, Dompok however is of the view that there are people who start learning a language not necessarily hoping that it can secure an economic advantage for them.

“People are also attracted to learn another language for social, communication, academic reasons and so forth.”

While the education system plays a crucial role in empowering the language among students, he believes that it can actually begin at home through family upbringing.

“Most students get an early grounding in the language at home, that’s how they are able to master the language.

“However, students can formally learn more about the language in school. Therefore, it is important to encourage our children to start learning and speaking the language at home,” he asserted.

Even so, Dompok admitted that this is easier said than done as even he finds it challenging in his own family.

“My family members can speak the language, in varying levels of fluency, but the vocabulary is not very strong,” he said.

Reiterating the importance of literature in language development, Dompok said he encourages people who are well-versed in Kadazandusun to write books that may interest learners of the language to read and assist them in learning the language.

He stated that reading could also help people understand more about a timeline or setting, be it contemporary or cultural.

“I read a book written by Scholastica Lanjuat, an author from Penampang, a long time ago. I was asked to write a foreword. When the manuscript was given to me, I thought it would be a real struggle to finish reading it. There were not many novels written in the language then.

“But when I read the book, it got more and more interesting because she writes against the background of Penampang during the era of North Borneo in the 50s and 60s when rice was still planted and harvested in an old-fashioned way in the Penampang district.

“The language that the author used captured the penchant for native speakers to include colloquial terms in their daily conversations. She chooses words like ‘insim’ which translates to ‘auntie' or in native Tangara, ‘inai’.

“In this little passage of the book, it reveals perhaps the early influences of the Chinese in the area. Firstly, cultivating rice with ploughs pulled by animals, and secondly, words or phrases in Chinese become a colourful infusion into the native language. Perhaps carrying the paddy in a sack on the back of a buffalo was a local ingenuity! So, a novel can be also served as a throwback to a bygone era.

“I do not think our children now appreciate that, but there will be a yearning for that type of literature in the future. This is what we want to leave to the next generation, that is why it is very important that there is literature,” he explained.

Due to his devotion and aspiration to preserve the Kadazandusun language, an award called the Tan Sri Bernard Dompok Kadazandusun Language Literary Award was introduced by the Kadazandusun Language Foundation (KLF) to dig out the talents of the Momogun people in writing Kadazandusun literature.

As former President of UPKO, Dompok said Sabahan native languages are a core part of what the party started with, and it is a party that has a connection to the past.

“Even the name ‘UPKO’ conjures an image of an earlier stage in the formation of the country and the challenges that the early leaders faced in trying to steer the state and the country along the path that was laid out by the founding fathers.

“Freedom of religion and the preservation of the North Bornean cultures and traditional customs have become an important part of the struggle of the party. Native languages are part of it. So, it is a legacy that UPKO should find worthy of protection.”

Dompok said another thing that UPKO can pursue is the follow-up for the Native Court to be a legitimate part of the judiciary, equal in status to the Shariah and Civil Courts.

When asked if a special ministry on the Anak Negeri portfolio could be formed in the future as it had in the past, he said such establishment is important but even without it, tasks that should be handled by this ministry can be assigned to other ministries, as long as a body that tends the Native affairs is formed.

“When I was in the government when Datuk Najib Razak came in as the Prime Minister in 2009, I brought a group of ministers to see him to discuss certain matters, including the government policies for the Bumiputera minorities in Sabah and Sarawak.

“I also asked if the PM could support the establishment of a Native Court System that is at par with the other courts in the Judiciary. Principally, it was agreed upon.

“Tan Sri Abdul Gani Patail who was the Attorney General of Malaysia also agreed to look into legal requirements which have to be satisfied and the mechanics of implementation. Tan Sri Richard Malanjum who was the Chief Judge of Sabah and Sarawak then was also supportive of the idea and so I thought it would happen.

“However, I was not so lucky during the election and so as they always say, the rest is history!” he said.

What did happen was the preparatory work. Dompok managed to secure funding for the Institut Latihan Mahkamah Anak Negeri (IMAN) which was to house, among others, the training centre for native chiefs, village chiefs (ketua kampung), and the Secretariat for the administration of native affairs. Successfully completed, it is now waiting in Penampang to be utilised fully for its intended purpose.

During his tenure as the Chief Minister of Sabah from May 1998 to March 1999, Dompok embarked upon the establishment of The Native Affairs Council.

The Enactment to facilitate its formation was passed in the Sabah State Legislative Assembly.

Again, as luck would have it, he lost in the state general elections. And again, his successors in office did not see the importance of its formation and nothing much came out of it.

The present State Government has appointed a new Chairman in the person of Dr. Benedict Topin and a revival of expectations has emerged, and that the new Council members will do justice to the formation of the Council.

Comments